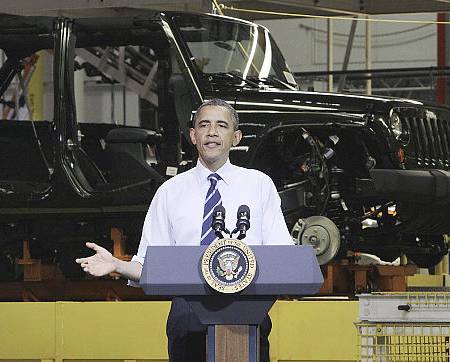

You’d think the Obama campaign had confused Michigan and Ohio with Iowa and New Hampshire. As his 2012 Republican challengers flooded early primary states last month, the President instead headed to where he could stand beside beaming auto executives and watch proud workers toiling on once-idle assembly lines. The Obama administration and the industry have been making a hard media push this summer, celebrating the auto bailout as a big win — for the politicians who supported it, for the economy that they claim needed it, and for the taxpayer who still begrudges it.

To this day, Americans remain unconvinced of the bailout’s wisdom, and fewer than half of likely voters are optimistic that we will be repaid the total $80 billion we coughed up. And if Americans were more familiar with one underreported aspect of the bailout — the rescues of the automotive financial firms — they’d feel even less enthusiastic about joining the party in Detroit and Washington.

Between 2008 and 2009, we taxpayers forked over $17 billion to GMAC (now Ally Financial) and $1.5 billion to Chrysler Financial under the vague theory that they formed an essential part of the auto industry. In doing so, we preserved two entities that, like the banks and mortgage companies, were making subprime loans to consumers: high-interest loans made to high-risk borrowers. Chrysler Financial has paid us back, but despite making more auto loans than any other company last year, Ally just delayed its planned IPO because it is not doing well enough to enable the government to reduce its majority stake.

To repay taxpayers and be profitable going forward, these institutions have concluded that they must expand their portfolio of subprime loans, and they are doing so with gusto. Last month, the credit scores of those buying new cars hit a five-year low. Overall, lending to buyers with credit scores under 680 has been rising quarter after quarter so that four out of 10 auto loans today are subprime. That’s right: 42 percent of Americans — including many economically vulnerable people — are taking on auto debt at high rates of interest, making purchases set to become albatrosses dragging down their tissue-thin household budgets.

Although these lenders assert that subprime auto loans do not pose a risk to the financial system similar to that presented by subprime home loans, this is distinctly disingenuous. Yes, the auto loan market is smaller than the mortgage market, and yes, lenders can quickly repossess cars against which loans are made. But this by no means ensures that these companies won’t fail or find themselves in need of another bailout. Subprime auto lenders might not be the principal driver of a financial crisis, but they absolutely contributed to and suffered from the last one. Like the mortgage lenders, they bundled, securitized, and sold off car loans into a market that collapsed, and GMAC actually diversified into home loans at the bubble’s peak. Obviously, these firms can feed into -- and falter from -- the next crisis as well.

Aside from potentially causing major damage to the economic system, subprime loans also end up hurting their supposed beneficiaries. Subprime lenders enjoy playing the hero, trumpeting that they provide struggling Americans the opportunity to buy a car. This might have some merit, if subprime loans were being made solely on modestly and fairly priced economy cars. Instead, lenders are taking the opportunity to maximize profit; people with lower credit scores tend to be sold cars at inflated prices and are subject to higher dealer interest rate markups.

The rationale for rescuing the two financial arms remains murky. In Overhaul, a memoir of his stint as so-called car czar, the best that Steven Rattner offers is that the “fincos” were part of the auto industry and that the collapse of the financial markets had “created havoc for the automakers.” From where we sit today, it is hard to know exactly what would have been the outcome of allowing them to fail.

Many car buyers, ironically, would have been better off. These companies provide most of their loans through dealerships, and car buyers usually benefit when they borrow instead from a neighborhood bank or credit union. Buyers who head into the showroom already financed are less likely to buy a pricier car than they need, are more assured of getting the best rate, and are less susceptible to sales or lending fraud.

But most are not so lucky. We spoke with a Rhode Island factory worker, Greg, who was convinced to take on more than $20,000 in debt for a sensational new pickup he bought under the Cash for Clunkers program. To keep up with his payments and avoid repossession, he had to take a second job driving a taxi.

Taxpayers would surely have been better off without the bailouts of the auto financial firms. Even if fully repaid, we will find we have enabled the re-bloating of our national auto debt.

It is easy to imagine how $18.5 billion could have gone instead to reducing the deficit or to sustaining or building our transportation system in more efficient and equitable ways. Preventing transit fare hikes, maintaining eroding infrastructure, keeping traffic and transit police on payrolls, funding investment in green transportation and complete streets, and working on creating jobs closer to the people who really can’t afford cars: The alternatives were a beautiful and bountiful lot.

Catherine Lutz, a Brown University anthropologist, and Anne Lutz Fernandez, a former marketer and banker, are the authors of Carjacked: The Culture of the Automobile and its Effect on our Lives (Palgrave Macmillan).