Cross-posted from Mobilizing the Region, the official blog of the Tri-State Transportation Campaign.

A December study from the U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO) finds that, well, there’s not much government accountability when it comes to how states spend federal transportation funds. Despite the existence of a federally mandated transportation planning process, the federal government offers no clear goals for state spending and there’s no clear way of knowing what benefits the public gets in return for such spending. GAO surveyed all 50 state DOTs (as well as DOTs in D.C. and Puerto Rico) and identified common challenges and opportunities to transition to a more “performance-based” transportation planning framework.

Politicized State Planning, Rubber-Stamp Federal Oversight

Federal law requires all states to conduct a long-range transportation plan and a statewide transportation improvement plan (STIP). The long-range plan is supposed to cover the state’s strategic vision and direction for a 20-year period, but varies in content from state to state because there is really no requirement about what each state puts in it or when the plan gets updated. In fact, 10 states have not updated their long-range plans since the last federal transportation bill authorization in 2005.

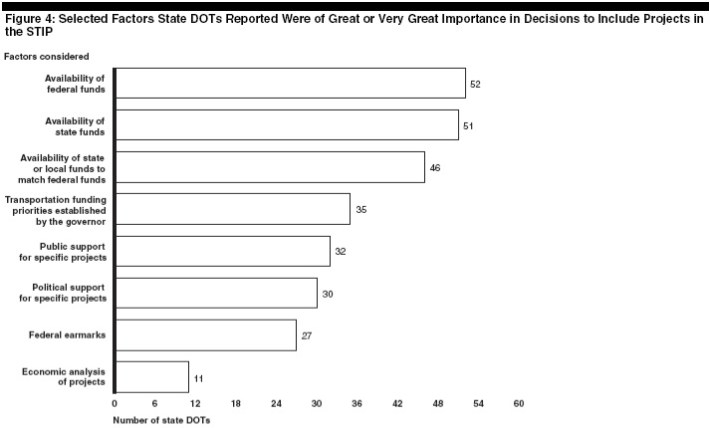

The statewide transportation improvement plan, on the other hand, is developed every four years by state DOTs and is the project-by-project, itemized blueprint for how each state spends federal transportation dollars. What factors are most influential when it comes to selecting projects for the STIP?

“Funding and politics,” according to GAO’s 50 state survey:

In fact, 35 state DOTs identified the governor’s funding priorities as a factor of great or very great importance in project selection. Only 11 gave the same weight to economic analysis (i.e. cost-benefit, cost-effectiveness, and economic impact).

Part of the problem, as GAO previously reported in a 2008 study, is that the current federal transportation bill is filled with a wide array of programs with “numerous and conflicting” goals and federal oversight of these programs “has no relationship to the performance of either the transportation system or of the grantees receiving federal funds.” As it stands, the feds do not require state DOTs to look at a project's impacts on fuel savings, travel time, greenhouse gas emissions, water quality, or public health. USDOT’s primary focus when it comes to state transportation improvement plans is process (i.e., did the plan allow for public review, did the plan demonstrate fiscal constraint, did it follow federal planning regulations?) and not outcomes (i.e., does this plan reduce congestion, does it maintain a state of good repair, does it improve mobility options for all?).

Outcome-Based Planning: It’s Not Impossible

Setting performance measures to track outcomes like livability, mobility or congestion is not straightforward, the GAO found, because there is no consensus across states on how these should be defined or measured.

But most state DOTs do use performance measurements in the areas of safety and asset condition. The GAO study found that this is due largely to federal requirements that state DOTs develop a highway safety plan with statewide goals and collect and report road and bridge conditions to USDOT. In other words, when the federal government sets specific guide posts, states follow.

Another example are the TIGER grants first unveiled as part of the stimulus package. USDOT required all grant applicants to conduct cost-benefit analyses that measured project impact on fuel savings, travel time, greenhouse gas emissions, water quality and public health. States were hardly dissuaded by these requirements; USDOT received an overwhelming flood of applications for TIGER I and II grant cycles that exceeded available funding by threefold.

GAO’s key recommendations to Congress echo what many transportation reformers are pushing for: That the next federal transportation bill establish national transportation goals and direct USDOT to work with states to develop performance measures, set targets to track progress toward goals, and change its oversight of statewide planning to focus more on outcomes. Informing taxpayers what they get in return for federal transportation investment is a goal that should cut across party lines.