If you're a sustainable transportation or antiracism advocate in the United States, you're probably heard the number $11,000 a lot over the last couple weeks.

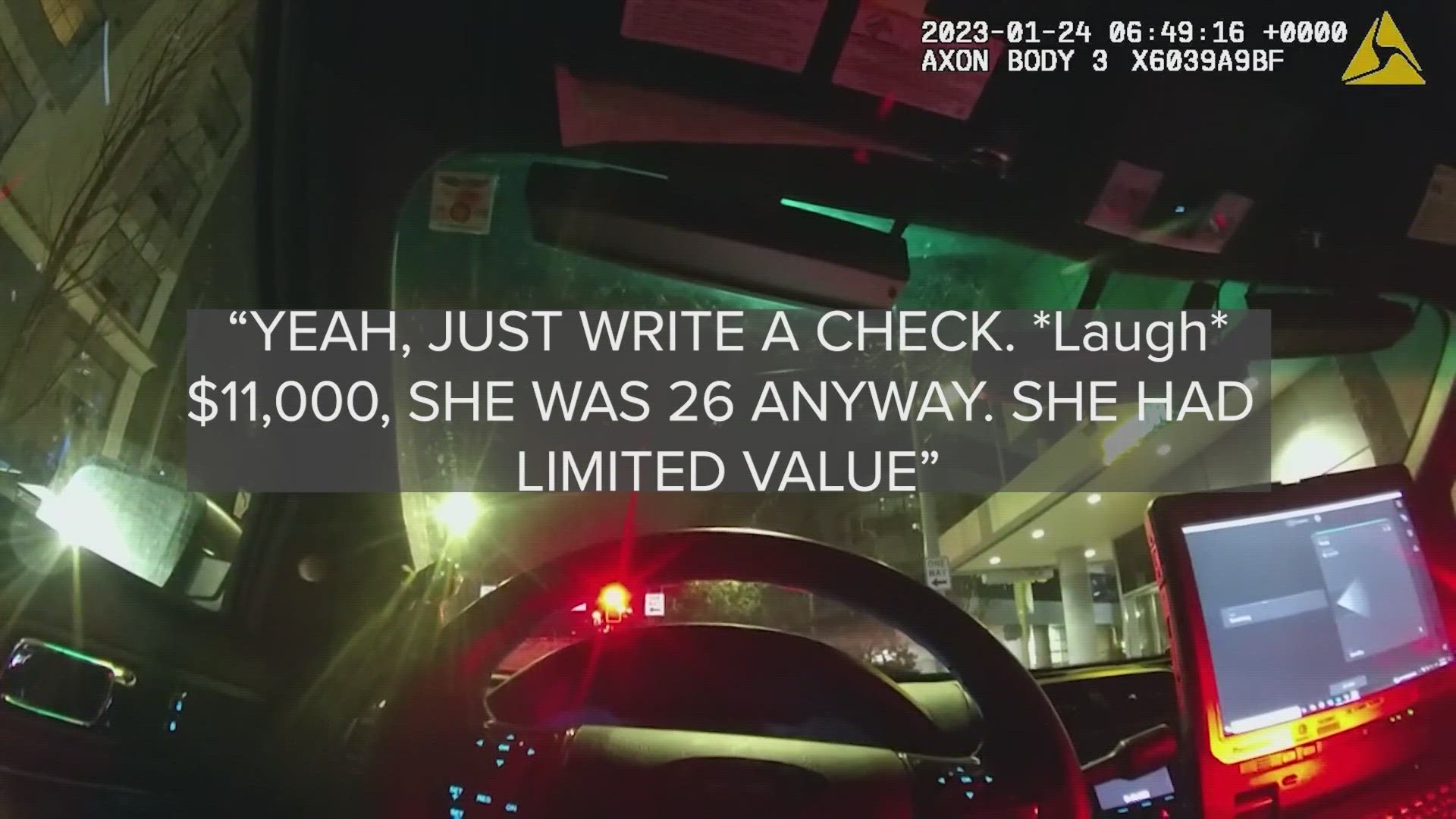

That was the number cited by Seattle Police Officer Daniel Auderer, who was unknowingly caught on tape following the killing of engineering graduate student Jaahnavi Kandula, 23, by Officer Kevin Dave, who was reportedly driving his police cruiser 74 miles in a 25-mile-per-hour zone.

"It's a regular person," Auderer says of Kandula, before erupting in laughter. "Yeah, just write a check. $11,000. ... She had limited value."

Auderer's comments touched off a wave of backlash when they were released by the department two weeks ago — a backlash that was not tempered by Auderer's statement that he "was imitating what a lawyer tasked with negotiating the case would be saying and being sarcastic to express that they shouldn’t be coming up with crazy arguments to minimize the payment."

Many members of the South Asian community — Kandula was from India — decried Auderer's comments as racist, chanting, "Who has unlimited value? Jaahnavi Kandula; say her name" at the site of her death. Some advocates pointed out that the deaths of BIPOC pedestrians are the result of larger structural issues that extend far behind Seattle; a 2013 CDC study found that despite the fact that Asians and Pacific Islanders experience some of the lowest rates of pedestrian deaths overall, AAPI women actually experience higher death rates than women of any other race, particularly among seniors — a discrepancy that has still been largely understudied.

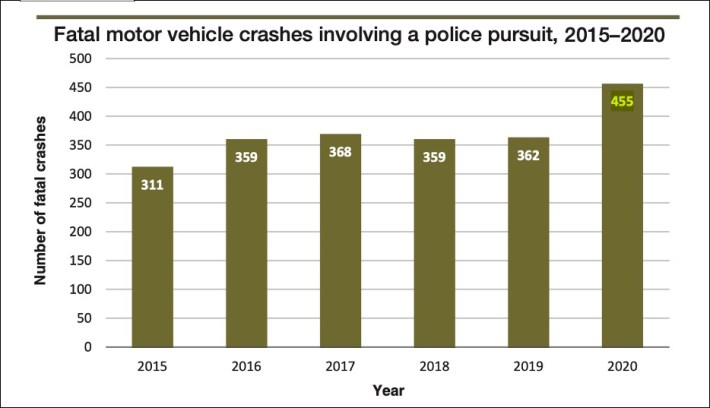

Others pointed to the case as evidence that the Washington legislature needed to revisit its policies regulating dangerous police pursuits, which it relaxed in May despite mounting national evidence that cruisers traveling at high speeds in pedestrian areas may endanger more people than the practice protects. A DOJ report released last Tuesday found that police-involved crashes are on the rise across America, peaking at 455 in 2020 and prompting watchdogs to recommend that agencies adopt dozens of restrictions on when officers are allowed to reach deadly speeds. (It is not clear whether those stats include crashes that occur when a police officer is not in direct pursuit of a suspect, like Officer Dave, who was en route to a reported overdose when he struck Kandula.)

Still others called into question Auderer's own alleged track record of violence on the job – which included 29 complaints of bias, unprofessional conduct and use of force — and the larger conversation about police brutality in the United States. Auderer is currently the vice president of the Seattle Police Officer's Guild; the person on the other end of the phone call was later identified as its president.

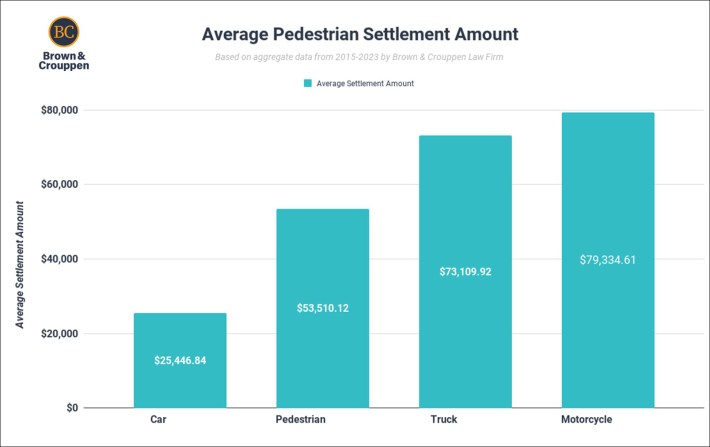

For some, though, one of the most outrageous things about Auderer's comments was simply that horrifyingly low number — $11,000 — and the very attempt to assign a dollar value to the life of a human being. And for thousands of families who lose loved ones to traffic violence every year, that brutal calculus comes out far closer to zero.

"My child wasn't worth anything," said Amy Cohen, executive director of Families for Safe Streets, whose 12 year-old son, Sammy Cohen-Eckstein, was killed by a driver in 2013. "People who are unemployed or homeless or otherwise deemed 'unworthy' typically aren't worth anything. The civil process is really biased towards people who, ironically, probably need [financial compensation] the least."

When drivers pay for killing pedestrians — and when they don't

In her work with Families for Safe Streets, an organization that fights for systemic solutions to traffic violence as well as better supports for victims and their survivors, Cohen has helped many families navigate the labyrinthine legal system that awaits Americans after a serious car crash. She says none of them has secured a settlement that could possibly compensate for the loss of a loved one who was priceless to them — and many don't even get enough to meet their immediate financial needs.

"People read about the giant settlements, and they think everyone is getting that," Cohen says. "But the vast majority of people get very little. And that's in addition to the horrible emotional toll [they endure]. Many people can't work, or they're not as productive after. ... A lot of people lose their jobs after a serious loss or injury. It has a horrible cascading effect."

Those "cascading effects," though, aren't always eligible for financial compensation — and even when they are, that money can be astonishingly hard to collect.

If a pedestrian is killed in a crash, the size of her survivors' settlement number is usually shaped by how much (or how little) insurance was carried by the driver who killed her, as well as his personal wealth and the court's ability to access it. It's shaped by the size of her medical bills and the length of time she spent suffering in the hospital before she died, while the survivors of victims who were killed instantaneously often have little recourse to sue, even to pay for funeral costs. And it's almost always shaped by how much the pedestrian herself earned in her lifetime, and whether she was using those wages to support dependents or simply herself — and if it's the latter, her other loved ones often aren't eligible for anything at all, even if their lives have been shattered.

"Some states have limitations on the collection of non-economic damages — that's the hole in your heart for not having the love and support of this person in your life," said Peter Wilborn, a Florida-based attorney and founder of the national Bike Law Network. "I lost my brother in a bike crash, and our mother didn’t listen to music for five years afterwards. That’s a heartbreaking thing, but it's probably not a case for not economic damages."

When the driver who killed a pedestrian is a police officer, Wilborn added that many states place strict caps on how much a victim can recover from government institutions, though he added that Washington's cap is "nowhere near $11,000." And while "aggravating circumstances" like whether the driver was speeding three times the local limit can change the size of a settlement that a jury awards, law enforcement officials like Kevin Dave may not be judged as harshly as a civilian driver – especially if the pedestrian is deemed at fault. Much of Auderer's hot-mic call was spent debating witness accounts of whether Kandula was in a crosswalk at the time of her death.

"The majority of our death cases aren't cops," added Wilborn. "They're criminal drivers: drivers on meth, hit-and-run drivers, drivers intentionally trying to buzz a cyclist, sometimes all of the above. Aggravating circumstances can change our assessment of human value enormously. But regardless of what the valuation is, you have to ask — is anything collectible?"

Wilborn said that he's pursued many cases in which he knew drivers or their insurance companies wouldn't pay, because it's symbolically important to families to know that their loved ones' lives had value. He warns, though, that not many attorneys are willing to do that.

"I’ve represented thousands of cyclists and whether they get justice or not is almost entirely dependent on the tenacity of their council ... If you don’t have a good spokesperson, or there's there’s not any money in the case, very few personal injury lawyers will do what zealous representation requires," he added. "The value we assign to a life isn’t just determined by the courts; it isn’t just determined by the insurance companies. It’s determined by whether the attorneys give a shit, period."

Falling through the cracks

For the families of people who die suddenly by traffic violence, those questions of collectibility often have far more devastating ramifications than most people realize. Cohen said she's worked with families who have lost jobs, businesses, and even become homeless in the wake of a serious collision, even when they were able to successfully mount a civil suit — and many weren't.

"I can't tell you how many calls our social work team gets from people who lost their homes, who can't work, who really fall through the cracks after a crash, whether they're lost a family member or they were the one who was injured," she added.

Even families that aren't completely financially devastated by a crash still often struggle in the absence of a meaningful settlement. Bobbi Koval learned that firsthand when her son Jack, 22, was killed by an off-duty police officer who struck him in a Manhattan crosswalk in 2016. The driver was not charged, despite the fact that witnesses say he had sped around several other motorists who had stopped to let Koval cross. The family spent years trying to clear Jack's name after inaccurate media reports essentially blamed him for his own death, not to mention untangling the countless loose ends left by his sudden loss.

"We had out-of-pocket expenses people don't think about," said Koval. "I mean, he was living in New York City when died, and his share of the rent was significant; we had to pay that. Luckily we could afford to pay to bring his body pack here. But what if we couldn't?"

At the time of his death, Koval was a recent graduate of Emory University and a new hire at an a boutique Wall Street firm making $85,000 a year, with the possibility of significant bonuses. But because he wasn't supporting any dependents at the time of his death — much like Kandula, who had a single mother she hoped to support someday, but who was instead left to repay her daughter's student loans — none of the potential income lost when Jack was killed was collectible in court, despite the fact that he had worked his new job for only four weeks, and was an only child who likely would have supported his parents' retirement someday. He also left behind five devastated cousins who thought of him much like sibling, and struggled with losing their bright, inquisitive loved one to a violent death.

"Primary breadwinners aren’t the only people who have a financial value," Koval added. "It’s about the family that’s grieving, and families have needs. [A settlement] could have meant therapy for my niece for the rest of her life; it could have meant medication to cope with trauma. … It’s not about getting a check so you can live comfortably. It’s a repayment.”

Today, Koval, Cohen and their fellow advocates at Families for Safe Streets are fighting for legislation in New York State that would make it easier for families to secure those repayments — and hopefully, avoid some of the other indignities to which the legal system subjects them. The Grieving Families Act would allow survivors to sue for grief and anguish following the loss of a loved one, and extend the time they have to file suit to three and a half years; it passed unanimously through both chambers of the legislature, but Gov. Kathy Hochul has yet to sign it. The Crash Victims Bill of Rights Act could also help extend more financial protections to families by requiring the state "produce a report for the Legislature to determine the adequacy of current compensation and services for crash victims", while also giving them the simple right to make a victim's impact statement in court and secure police reports quickly after crashes.

Cohen hopes both bills will pass, and someday, become a model for other states — because right now, there's "nothing else like them" in other American communities.

"It's about providing support and a voice to crime victims, and it should be extended to crash victims whether or not the driver is charged," Cohen added. "[It's about getting them access to] a whole array of supports to help people as a payer of last resort — particularly low income people who are most devastated by this crisis."

An admission of guilt

In their interviews with Streetsblog, both Koval and Cohen stressed that fear of financial penalties alone won't end the national traffic violence epidemic, and that they're still fighting for safe infrastructure, safe speed limits, and other structural solutions. In concert with other prevention measures like infrastructure, though, that fear might serve as some deterrent — particularly for city leaders who would write off a pedestrian's life for a few thousand dollars.

"Every number and every death is so much more than just a statistic," said Cohen. "It devastates families and communities. [What Officer Auderer said] was an incredibly heartless and painful comment, especially to those of us who know the suffering firsthand."

For Koval, securing a settlement from the officer who killed her son was less about the money and more about protecting Jack's legacy. After a grueling seven-year legal battle, they just reached an agreement with the driver this year: he will pay $100 a month every month for 10 years to benefit an overnight camp that helped shape Jack into the person he was.

"It’s an admission of guilt that he killed our son," she added. "That’s all we really wanted ... It isn’t about a certain amount of money. It’s about holding that person accountable, and making them look in the mirror."