With e-commerce sales booming and the demand for speedy shipping on the rise, the impact of ultra-fast deliveries on our roads and environment has become increasingly apparent. The fallout looks like a veritable armada of delivery trucks triple-parking in your neighborhoods.

E-commerce sales increased by about 43 percent during 2020 alone, and by the end of 2021, a full 46 percent of Americans had Amazon Prime memberships. Recent consumer studies elaborate that the majority of online shoppers expect their goods delivered quickly — i.e., grocery orders placed by midnight arriving on your doorstep the next afternoon.

All that ultra-fast delivery, though, comes at a high cost in carbon emissions, traffic congestion, labor, and more. And those negative outcomes have to date gone largely unregulated.

Streets are a public resource, paid for by the people, and right now, delivery vehicles are taking up more than their fair share under a system that isn’t even profitable. With more interest than ever in fair share taxes — i.e., the newly passed “Millionaire’s Tax” in Massachusetts — as well as balanced street space and livable working conditions for delivery drivers, it’s time for a more common-sense approach to Geekwire. From the original article: "The loss in the rest of the business [not related to Amazon Web Services] shows how much Amazon is spending in its e-commerce business in the latter days of the pandemic to ensure fast delivery times despite labor shortages, supply chain constraints and inflation. Amazon said costs were about $4 billion higher than normal in the quarter due to those issues." - Todd Bishop." class="alignnone size-medium" />regulating rapid deliveries in U.S. cities, with policy that recognizes the merits of online shopping, but prices it fairly to address the burdens it places on our shared spaces.

Jeff Bezos doesn’t want you to know this, but many businesses lose money on same-day shipping. Rising interest rates are showing us the true cost of convenience delivery services like Lyft, Uber, DoorDash, and Postmates now that venture capital funding is drying up.

It’s not a big surprise if you think about it. After all, it’s inefficient to send a whole truck out to deliver just a few packages to disparate destinations, especially when you factor in record high gas prices and traffic congestion. Moreover, per-package greenhouse gas emissions are on average about six times higher for customers who select one-hour versus 24-hour deliveries.

To address this, I propose that states should tax same-day deliveries. A delivery tax is a low-hanging fruit that would nudge consumers towards making more sustainable decisions without taking away their ability to order goods and have them appear at speeds that would make previous generations’ heads spin. Already, 65 percent of American consumers have expressed that they would be willing to pay more to get their goods faster. Why not take advantage of that value for public benefit?

The pandemic laid bare the stratified economic system that we live in, wherein some people order groceries, and others deliver them. A delivery tax could help redress some of that inequity by putting money towards shared infrastructure that benefits low-wage essential workers.

Some of that most important shared infrastructure are shared transportation options. Decades of research show that the best way to cut down on traffic congestion is by providing high quality transit that’s affordable to all, yet transit is a chronically underfunded public good (versus driving lanes and parking, which have been subsidized since the invention of the automobile). The scale of a well-functioning system – one in which trains and buses reliably come at least every 15 minutes – costs more than affordable fares can support, but funding proposals such as higher gas taxes or congestion charges have not been politically popular in the past.

On the flip side, with the climate crisis and economic insecurity top of mind for many, the voting populace may be more game to make billionaire e-commerce moguls pay their fair share for their high carbon impact. If directed to transit agencies, a same-day delivery tax could help critical transportation providers struggling to meet operations funding gaps due to lack of post-pandemic ridership recovery, and improve service to boot.

Governors' offices can also encourage municipalities to plan for more sustainable delivery networks. Done right, nudging consumers towards multi-day deliveries could represent a big opportunity to reduce carbon emissions from short car trips: the advocacy group Consumer Ecology created a tool to estimate the carbon footprint of shipping and automobile-based grocery trips, and found that the average American generates just under 100 kg of CO2e per year by grocery shopping. Multiply that by a population of 331 million, and we get 33,100,000 tonnes of CO2e/year, which is about five percent of the 2020 national carbon footprint. Further, the air quality impacts of all of this driving are disproportionately borne by neighborhoods with higher percentages of people of color due to our country’s racist highway planning history.

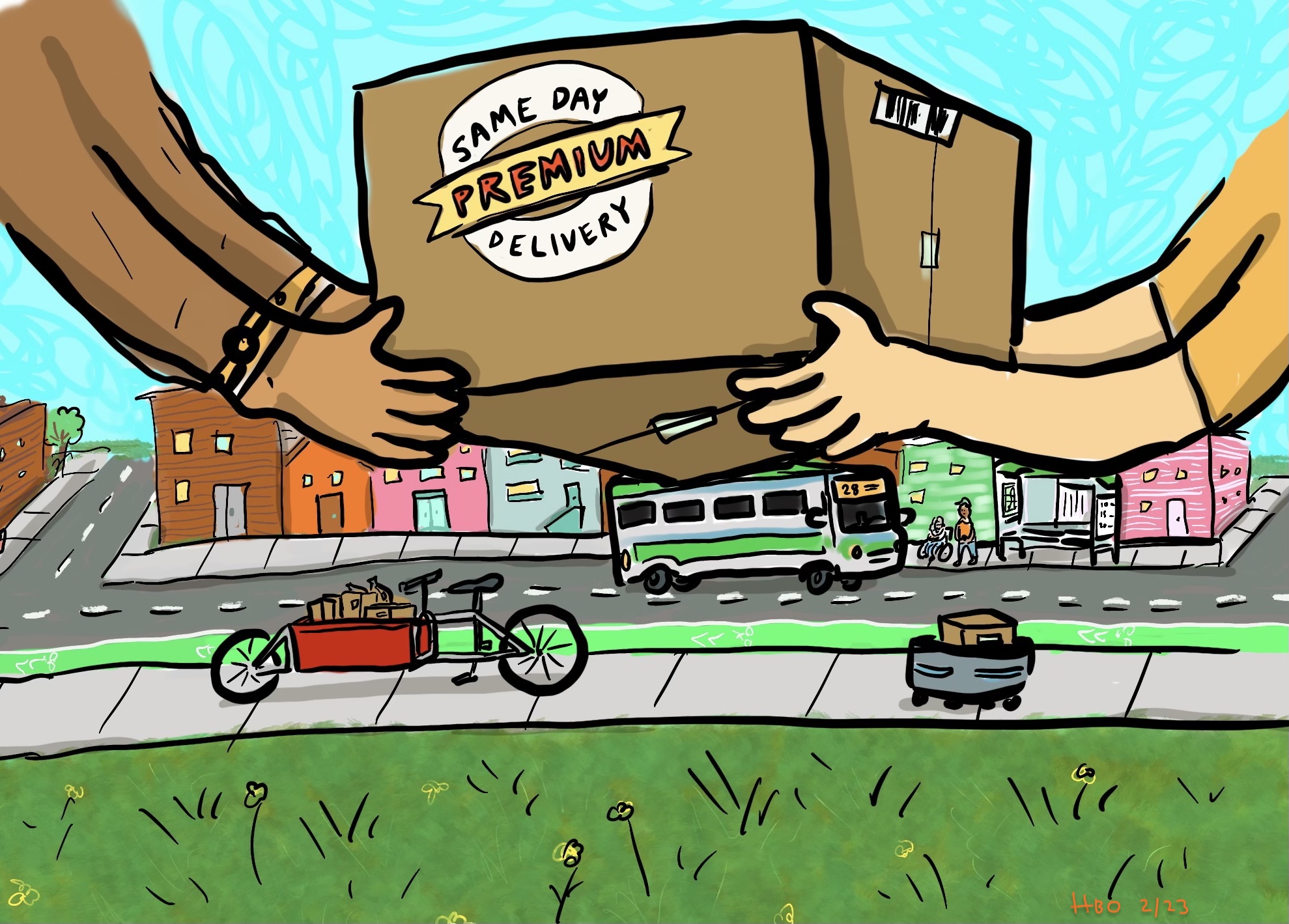

An optimized delivery system would string trips together more efficiently by utilizing centralized neighborhood delivery nodes, conscious curb management, and green micro-mobility solutions to carry packages that last leg of the journey. Distribution hubs could look like your familiar neighborhood Amazon fulfillment center; they might even look like a local grocery store. Trucks should be reserved for long distance routes, then directed to designated loading zones where goods get transferred to a finer-grained local delivery network. Loading zones can be prioritized for electric trucks to help aid in the decarbonization of regional shipping. E-cargo bikes (which studies show are significantly faster than vans in city centers), drones, and adorable delivery robots are much better suited for bringing goods that last mile to your doorstep.

Although the typical narrative is that automation of an industry leads to job loss, the supply chain is a unique beast. The average truck driver is 50 years old, and one in three are over age 55, and the folks who load and unload trucks skew older as well. Many of these workers will retire in coming years, yet there is a national labor crisis in recruiting new workers, in part because these jobs are unattractive when many delivery companies like UberEats and DoorDash withhold benefits like health insurance from their employees. Delivery will still need labor, but those jobs might look different in the future.

To those for whom this proposal is reading suspiciously free market-techno-utopian rest assured: embracing automation and preserving fast shipping options in no way precludes also striving towards more bread-and-butter approaches to sustainable urban planning, like developing “15-minute” walkable mixed-use neighborhoods, local food chains, and farmers markets.

Rather, getting ahead of the rapid delivery trend is important because it gives states the best chance to harmonize consumer demand and funding needs to give us good outcomes. We’re seeing what happens when we leave the market alone today, and it’s not pretty.

Government regulation can push private delivery innovations in the right direction to achieve wins for every stakeholder. Businesses will save money, communities will see reduced greenhouse gas emissions and reclaim their curb space, and consumers can still get their groceries overnight — but will be encouraged to default to more efficient and sustainable shopping.

Hazel O’Neil is an illustrator, graphic designer, and assistant planner who lives in San Francisco, CA. She is the creator of the short documentary, My Way is the Highway, an animated history of the US Interstate Highway system.