U.S. PIRG and the Frontier Group are on a mission to explore the downward trend in driving. In a series of reports, they point to evidence that it isn’t just a temporary blip, but a long-term shift in how Americans get around. Today, the two organizations released a new report, “Transportation in Transition: A Look at Changing Travel Patterns in America’s Biggest Cities,” which shows that these changes are happening in regions all over the country.

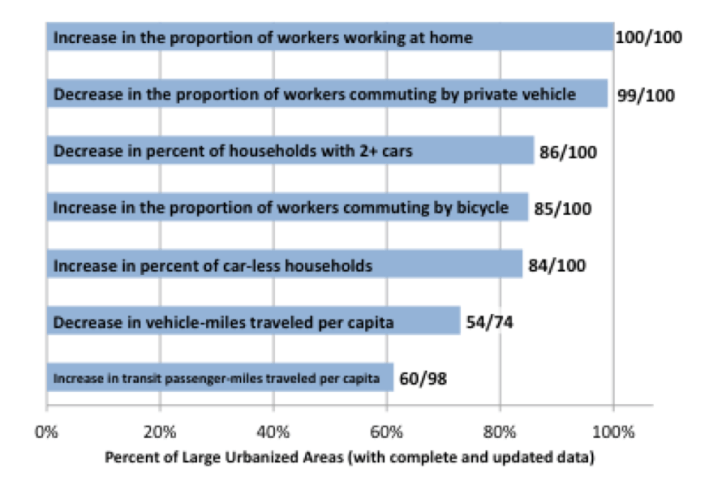

In 99 of the nation’s 100 largest regions -- the cities and suburbs that are home to more than half the U.S. population -- fewer people got to work in a private vehicle in 2010 than in 2000. In the vast majority of those areas, households are shedding cars while more people are getting on the bus and taking up biking. These 100 regions are the engines of the U.S. economy and where most of the nation's population growth is happening.

Since state DOT data collection leaves much to be desired, PIRG and Frontier Group encountered some situations where they couldn’t do an apples-to-apples comparison. As a result, they examined vehicle miles traveled trends in only 74 of the 100 largest urbanized areas. In 54 of those, VMT had dropped. Across the country, mileage is down 7.6 percent per capita since 2004.

"Each city has a different story," U.S. PIRG’s Phineas Baxandall said in an email. "Sometimes the stories are hard to see because the data is messy, but the overall picture suggests real changes in how people get around."

The report kicks off with a lovely tale about one city's fight to keep a highway from destroying downtown:

When Madison, Wisconsin, was given the opportunity to bring the interstate into the city in the 1960s, local officials decided to keep its downtown highway-free -- they believed that a highway running through Madison’s narrow downtown isthmus would make the city less attractive. But without the Interstate, city officials needed to make sure that residents had access to other modes of transportation to travel down-town. So city planners sought to build a multimodal transportation network that promoted bicycling, public transit and walking.

And guess what? Those investments are still paying off. As attitudes about transportation and urban living shifted over the past decade and more people decided to explore life outside the automobile, Madisonians had lots of good options to choose from. On average, each city resident drove 18 percent fewer miles in 2011 than in 2006 -- from 8,900 miles down to 7,300. Meanwhile, biking to work soared 88 percent in the last 11 years, and bus ridership is way up.

U.S. PIRG and the Frontier Group encourage other places to follow Madison’s lead. Madison started investing in multi-modalism in the 1960s and 70s, when driving was still ascendant. Today, as Americans embrace transit and active transportation in greater numbers, driving declines, and new roads become increasingly poor investments, those same strategies should seem like ordinary common sense.

“Instead of wasting taxpayer dollars continuing to enlarge our grandfather’s Interstate Highway System,” said Baxandall, "we should invest in the kinds of transportation options that the public increasingly favors.”

Where did car commuting drop the most? Some usual suspects, sure -- New York, Washington, San Francisco, Portland. But Austin is up there at number three, and Poughkeepsie, NY, is number four.

Commuting isn’t everything -- it’s only 28 percent of miles driven -- but data for non-work-related transportation is hard to come by. And since so many places build road capacity to withstand rush hour traffic, it's important to understand how Americans get to work. In 1960, 64 percent of workers commuted by car. By 1980, it was 84 percent. By 2000, it was up to 87.9 percent.

And then it started dropping, ever so slightly. The 2007-2011 American Community Survey shows that 86.3 percent of workers commuted by car during that time. And as this report shows, that downward trend happened across every single one of the country's largest regions except one: New Orleans.

New Orleans is an outlier in much of the data, since for much the period studied, the city was reeling from Hurricane Katrina. Some advisors even recommended that the report leave the city out altogether. VMT in the Big Easy is down a mind-blowing 22 percent, car ownership has dropped, transit ridership has risen -- yet it’s the only urbanized area in the country where more people are driving to work now than in 2000.

"In addition to the storm and the exodus, there are the aid workers, many of whom don’t own their own cars and travel long distances because of housing shortages at the city," Baxandall said.

The report also repeats what the organizations asserted a few months ago: that the recession and unemployment don’t fully explain the drop in driving. Cities with the biggest increases in unemployment and poverty rates aren’t the same ones that have turned away from cars in the greatest numbers.

In addition to revising transportation plans and investing more in efficient modes, authors Baxandall and Benjamin Davis hope governments at all levels will improve their collection and transparency. They couldn’t adequately compare some cities’ driving trends because their state DOTs hadn’t updated their “urbanized area” maps to match the 2000 census. There’s no good way to measure VMT per capita on a regional scale if population counts and VMT counts are measuring different geographic areas.

Data collection is also far too slow and infrequent. U.S. Transportation Under Secretary Polly Trottenberg often tells an anecdote about meeting with the big brains who run Google’s traffic program, who were sheepish about admitting that there is a lag in the data -- “but it’s not 60 seconds or anything.” She tells that story to highlight the absurdity that the government is still using data from 2008 to set policy.

With transportation behavior in the midst of such a fundamental shift, states and cities need to monitor it far more closely to get a grip on how to set policy. More importantly, they need to change how they plan and build transportation systems, before they waste too much more money on antiquated infrastructure.