Friday was the Obama administration's reporting deadline on a slew of scheduled budget cuts set to take effect January 2. I guess the president was busy or something, because his administration blew this deadline. Now they're promising to have some answers this week.

Here's what they're tasked with: The administration needs to put some concrete numbers to a vague, but very intimidating, outline for budget cuts that were "triggered" by the failure of the supercommittee to come up with a plan of its own. Last summer, the Republicans insisted on cuts in exchange for raising the debt ceiling, but no one -- including the supercommittee -- could agree what to cut.

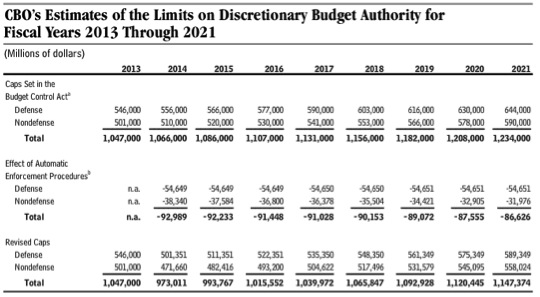

The automatically triggered cuts, known as "sequestration," are a sort of nightmare scenario for all sectors -- and that was exactly the intent. They were supposed to be horrific enough to rally both parties to agree on something. But even the specter of deep, across-the-board cuts wasn't enough to trigger some bipartisanship in Washington. The sequestered cuts will have to shave about $90 billion a year off the budget through 2021.

Without seeing the details the administration is due to produce, it's hard to know what the sequestration would mean for transportation. The sector is partially protected by the fact that many core transportation programs are funded out of the Highway Trust Fund, a separate funding source that, ostensibly, has nothing to do with the overall budget deficit.

But, due to the insufficiency of gas tax receipts to fund the nation's transportation needs, the government has supplemented the fund with other money -- and there's no saying that money couldn't be vulnerable to the funding cuts. And, as Larry Ehl of Transportation Issues Daily warned in an email, "Congress can change the rules of the game at any point." Even though Highway Trust Fund programs are exempt as the law is now written, Ehl says, "I've always felt it would be really hard for Congress to allow big funding cuts to social programs while saying, 'Gee, the law says we can't cut transportation.'"

Then there are the transportation programs that fall outside the Highway Trust Fund. They include New Starts capital grants for transit, Amtrak and other passenger rail funding, TIGER grants, and the Office of Sustainable Communities (which has already seen its funding axed for this year).

Agencies could have very little say over how to distribute the cuts. According to a Center for American Progress analysis of sequestration as it relates to the Pentagon:

Most budget analysts who have examined the issue believe that each ship funded in the Navy budget would be defined as a separate activity. As a result, if the Navy were budgeted to issue contracts on 10 ships in fiscal year 2013, then it would not be permitted to cancel one of the ships but would have to apply the cuts equally across each of the 10 ships.

That's an awfully inefficient way to cut programs, but it might be what ends up happening. And so U.S. DOT may be spared the heinous job of figuring out how to squeeze blood from a stone and instead just chop the stone into pieces, willy-nilly.

The administration has said its guidance on the cuts will come late this week. But meanwhile, the House is planning to vote to do away with the whole plan. Republicans are mostly upset about the cuts to national security programs, which Mitt Romney has used to attack Obama for weakening the military.

It's a little disingenuous -- the Budget Control Act, which mandated the cuts in the event the supercommittee couldn't do its job, was passed with the approval of the majority of Republicans in the House.

Another shot at a different way of doing budget cuts might not be a bad thing, given the potential consequences of the sequestered cuts. But would another budget-cutting showdown be more productive than the last one? Every time people in Washington sit down to try to reduce the deficit, the whole country ends up tangled in a stomach-churning mess of partisan name-calling, utter panic, and confrontations over the soul of America. Who needs that?