‘We’re Luring Bicyclists To Their Deaths’: Husband of Diplomat Killed While Cycling Turns Anguish Into Advocacy

12:05 AM EDT on September 1, 2022

Image description: Sarah and Dan Langenkamp pose with their two young sons at a swimming pool. Photo: GoFundMe

The husband of a U.S. diplomat who survived the war in Ukraine only to be killed in a car crash as she biked on a Maryland road is raising money to stop other families from having to endure similar tragedies — and urging the public to reckon with an epidemic of traffic violence that's left his children without a mother.

Last week, Sarah Langenkamp, 42, was killed when the driver of a flatbed truck turned into a parking lot along the 5200 block of five-lane River Road in Bethesda, Md., passing through the unprotected bike lane in which she was traveling, and running her over.

"I’m livid about the way that Sarah died," said Dan Langenkamp in an interview with Streetsblog. "This just didn’t need to happen. Cities are, rightly, trying to make themselves more livable for those that do not want to rely on cars — but at this point, we as a society are only beginning to realize that we can’t do it by just throwing paint on the streets... We're luring bicyclists to their deaths."

The Langenkamps, who were both highly accomplished diplomats for the U.S. State department, had moved back to the greater D.C. area just weeks before, following a recent assignment in Ukraine. Sarah and her family — husband Dan, as well as the couple's eight year-old and ten year-old sons— were ultimately forced to evacuate Europe, but not before Dan says Sarah "almost singlehandedly" coordinated the shipment of key military supplies to Ukranian forces within days of the Russian invasion. Their sons, who were briefly separated from their parents when the children went to live with relatives during most dangerous days of the siege, later became the subject of a viral news story about the boys' efforts to fundraise for Ukranian refugees.

At the time of the crash, Langenkamp had been reunited with her children and was returning from an orientation event at their new elementary school. She never made it home.

TONIGHT on @WUSA9: Husband of the US diplomat killed while riding a bike in Bethesda speaks out. While he mourns her loss, Dan Langenkamp, a State Dept employee, is calling for safety changes for bicyclists. They just moved here three weeks ago after evacuating Ukraine. @wusa9 pic.twitter.com/dBed8UdR2K

— Matthew Torres (@News_MTorres) August 30, 2022

Though Sarah Langenkamp's legacy is undoubtedly remarkable, the circumstances surrounding her death are all too familiar.

Nearly 1,000 cyclists died on U.S. roads in 2021, a total that's been climbing almost every year since 2010. And according to federal data, a staggering 58 percent of those fatalities happen on wide, fast arterial roads like the one where Langenkamp died — and another 17 percent happen on collector roads, which are often designed to similarly dangerous standards. Both types of thoroughfares are often carved directly through residential and commercial areas that people without cars rely on.

In Langenkamp's case, her route took her through a particularly notable gap in the city's bikeway network, which required her to travel amongst 35 mile per hour car traffic in order to access the disconnected segments of the protected trail system nearby. That lapse left her vulnerable, despite being an experienced cyclist who had cycled all over the world.

"Sarah and I have ridden our bikes on roads in Ukraine, in Uganda, in Cote D’Ivoire, but I feel more endangered on roads in the D.C. area than I did [in those countries]," Dan added. "I cannot tell you how many times we have almost been in crashes here because of the carelessness of drivers."

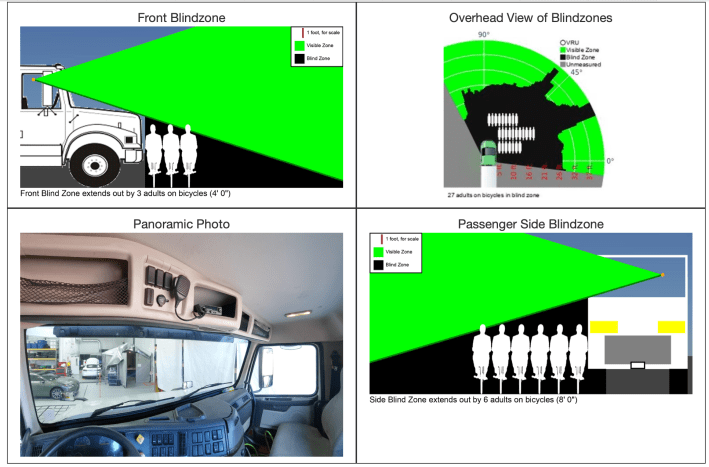

Dan Langenkamp also cites vehicle design as a factor in his wife's death. The 2013 Volvo commercial truck which struck her was so large that he believes the driver, who has not been identified by police, may not have physically been able to see her — though he doesn't accept that as an excuse.

"Why aren't there laws that say to trucking companies, you have to have sensors on the side of your truck if you can’t see down to the pavement or the sidewalk beside you?" he added. "Why aren’t there laws that say, if you have any questions about visibility, you have to make a full stop before you turn?"

Pedestrian detection sensors are available on many trucks — Volvo itself will begin offering them next month — but federal regulators have been slow to require the technology on even the largest commercial vehicles, not to mention dangerously large civilian vehicles like pick-up trucks and SUVs. They also have yet to mandate so-called "Direct Vision" standards, which would make it easier for truck drivers to see their surroundings without an advanced warning system.

A calculator developed by U.S. DOT's Volpe Center estimates that a 2012 Volvo commercial truck, which is similar in design to the one whose driver killed Langenkamp, can fit a total of 27 adult bicyclists in its front and side blind zones. The truck itself weighs at least 13,000 pounds.

"The public needs to understand that these deaths are incredibly violent," added Dan. "We cannot show the public her body because it’s so badly damaged. They won’t show me her body because it was so badly damaged. The people on the crash site are traumatized by what they saw. And my sons broke down on the way to school when I told them that they can never see their mother again."

Dan Langenkamp hopes that the money he's currently raising in Sarah's memory can help advocates push for policy solutions that will spare other families the pain he and his children have endured, though he's not yet sure exactly what that will look like. He's considering starting a foundation, contributing to the work of road safety organizations he admires, or pushing for tech companies to make simple but potentially life-saving changes, like adding bicycle safety advisories on popular navigation apps. The fundraiser blew past its initial $50,000 goal and had reached over $160,000 at the time of publication.

In the meantime, he's simultaneously navigating a difficult new reality as a single father who may no longer be able to manage the 12-hour work days of a diplomat, all while grieving the loss of his spouse of 16 years. Their home is filled with reminders of their life together, and especially their shared love of cycling; even the welcome mat outside their front door, he tearfully notes, is shaped like a bicycle.

"Biking is just so in keeping with who we are as people; it was a big part of our marriage," he said. "We were always deep believers in living lives that are green, and healthy, and humble...[My sons and I] are doing okay, but I think have to ask ourselves as a society: is leaving kids without their moms okay? Is it okay to rob children of their parents, and to do it in such a violent way that you can never be completely honest with them about how it happened? There needs to be a reckoning."

To contribute to Sarah Langenkamp's bike safety memorial fund, click here.

Kea Wilson is editor of Streetsblog USA. She has more than a dozen years experience as a writer telling emotional, urgent and actionable stories that motivate average Americans to get involved in making their cities better places. She is also a novelist, cyclist, and affordable housing advocate. She previously worked at Strong Towns, and currently lives in St. Louis, MO. Kea can be reached at kea@streetsblog.org or on Twitter @streetsblogkea. Please reach out to her with tips and submissions.

Read More:

Stay in touch

Sign up for our free newsletter

More from Streetsblog USA

If Thursday’s Headlines Build It, They Will Come

Why can the U.S. quickly rebuild a bridge for cars, but not do the same for transit? It comes down to political will and a reliance on consultants.

Wider Highways Don’t Solve Congestion. So Why Are We Still Knocking Down Homes for Them?

Highway expansion projects certainly qualify as projects for public use. But do they deliver a public benefit that justifies taking private property?

Kiss Wednesday’s Headlines on the Bus

Bus-only lanes result in faster service that saves transit agencies money and helps riders get to work faster.

Freeway Drivers Keep Slamming into Bridge Railing in L.A.’s Griffith Park

Drivers keep smashing the Riverside Drive Bridge railing - plus a few other Griffith Park bike/walk updates.

Four Things to Know About the Historic Automatic Emergency Braking Rule

The new automatic emergency braking rule is an important step forward for road safety — but don't expect it to save many lives on its own.