The Atlanta Beltline project isn't going away. Project staff want to make that clear. Sure, last week, Atlanta turned down -- by a wide margin -- a major transportation spending package that would have awarded $600 million to the Beltline project. But this project -- an innovative transit and trails corridor that will circle Atlanta's central city -- has seen big setbacks before, says Ethan Davidson, the Beltline's spokesman.

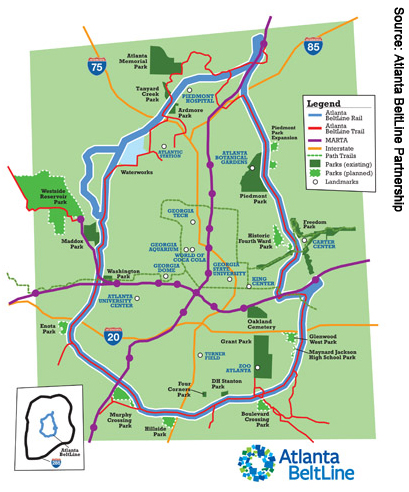

For roughly five years, Atlanta Beltline, Inc., the group charged with moving the project forward, has been collecting revenues from a special tax district that was conceived as the primary funding source. And the vision for an "emerald necklace" for urban Atlanta, first envisioned by a Georgia Tech grad student, is already starting to be realized, Davidson says.

Using revenues from the special tax district, plus money borrowed against future revenues, the group has already secured much of the right-of-way for the rail corridor: roughly 10 miles. In addition, 11 miles of trails, out of the planned 33, have been constructed, and many of them are open to the public. Between the tax revenues, bonding, a handful of government grants and some assorted private donations, more than $337 million has been raised.

True, that amount is shy of the $427 million they had hoped to raise by this time, said Davidson, but not bad considering the housing market crash that took place in the intervening years.

In addition to trail development, the Atlanta Beltline group is currently focused on establishing the right land use conditions for walkable, transit-oriented development, Davidson said. The Beltline group has plans to build some 4,500 affordable housing units around the corridor. About 120 of those have been built or are under construction.

In total, parks and greenway projects have already helped spur more than $1 billion in new development in the last five years within the surrounding tax district in total, Davidson said.

"Each new part of the Beltline that gets built has an immediate impact on the surrounding area," he said. "It transforms communities."

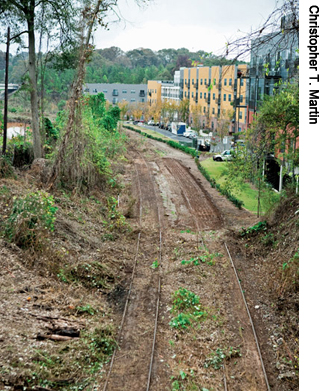

This project is all about restoring gaps in the urban fabric and connecting neighborhoods. Most of the Beltline area, which forms a circle two to three miles outside of downtown, is abandoned or underutilized rail right-of-way and industrial land. Much of the land was overgrown and unsafe. Eliminating these barriers will improve connectivity and help to eliminate unnecessary, short car trips between neighborhoods and commercial centers. The Beltline group has secured much of the land for the 300-acre Westside Park, one of the more ambitious greenway portions of the project.

Planners hope to complete their vision for 22 miles of transit and 33 miles of trails by 2031. The transit portion of the project is still in the early stages, and the passage of a new one-cent sales tax for transportation projects would have come in handy there, says Davidson. The $600 million promised to the Beltline would have built five miles of streetcar line along the Beltline loop, and five along city streets.

"With local money building five miles, it could have been leveraged [with federal funds] for us to build nine or 10 miles in 10 years," Davidson said. "That would have made us extremely competitive."

All in all, Davidson said he thinks the passage of T-SPLOST could have accelerated the transit timeframe by about a decade. But when the Beltline project began in 2006, they weren't counting on those revenues, so planners and politicians had always assumed the project would be feasible without it.

Meanwhile, political and community support for the project remains very strong, Davidson said.

"Of the 157 projects on that [tax referendum] list, this is the one that has the most community support; it has the most funding," said Davidson.

Following last week's vote, local advocates Citizens for Progressive Transit pointed out that urban voters were more supportive of additional transportation spending than those living in outlying areas. In the city of Atlanta, 59 percent of voters approved the measure, showing "that City of Atlanta voters are willing to pay for rail, bike, and pedestrian improvements," the organization said in a press release.

Davidson wouldn't speculate about whether a more focused, urban referendum to support the project would be feasible, saying that was up to politicians. Atlanta Mayor Kasim Reed indicated before the election that he wasn't eager to try a transportation referendum again if this one went down.

So the Beltline rolls on, with its original funding plan in place, focused on the long term. The group just completed its environmental impact statement and they have been careful to maintain eligibility for federal funds. They haven't identified exactly what the additional funding sources will be yet or seized on a very specific construction timeframe. But they hope to take advantage of New Starts, TIGER or other federal funding sources.

"We’re not sitting around crying," Davidson said. "We’re continuing to work because we have a lot of projects we’re working on right now. We’re going to be busy for years and years to come."