"America's infrastructure is slowly falling apart" went the headline of a recent Vice Magazine story that epitomizes a certain line of thinking about how to fix the nation's "infrastructure crisis." The post showed a series of structurally deficient bridges and traffic-clogged interchanges intended to jolt readers into thinking we need to spend more on infrastructure.

The idea that decrepit roads are caused by a lack of money is widespread. Vox's Matt Yglesias recently argued that the nation should borrow a bunch of money at low interest rates now and invest in an "infrastructure surge" that would help put idled construction workers back to work. Liberal crusader Bernie Sanders has introduced a bill in the Senate to spend $1 trillion on infrastructure over the next five years.

It's true that a surge of investment could be very helpful in building modern, high-capacity transit systems in American cities, or in constructing high-speed rail links between major metros. It's also true that the federal gas tax has been eroded by inflation for more than 20 years, so tens of billions of dollars in general fund revenue has been diverted to transportation spending since 2008.

But throwing more money at the problem overlooks the fatal flaw in American transportation infrastructure policy: The system is set up to funnel the vast majority of spending through state departments of transportation, and those agencies have an absolutely terrible track record when it comes to making smart long-term decisions. As long as state DOTs retain unfettered control of the money, potholed roads and decrepit bridges will remain the norm.

That's because the sorry state of American transportation infrastructure is mainly the result of wasteful spending choices, not a lack of funding.

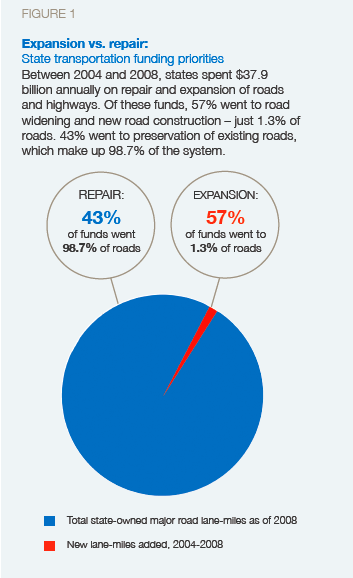

State DOTs' lack of fiscal discipline is nothing short of criminal. The chart on the right, courtesy of Smart Growth America, shows how states divided spending between new construction and maintenance from 2004 to 2008. States used most of their money -- 57 percent -- on new construction (projects like that massive but oddly empty interchange in Milwaukee, above, don't come cheap). Meanwhile, states used the 43 percent left over to maintain the remaining 98.7 percent of road infrastructure. This is a recipe for ruin.

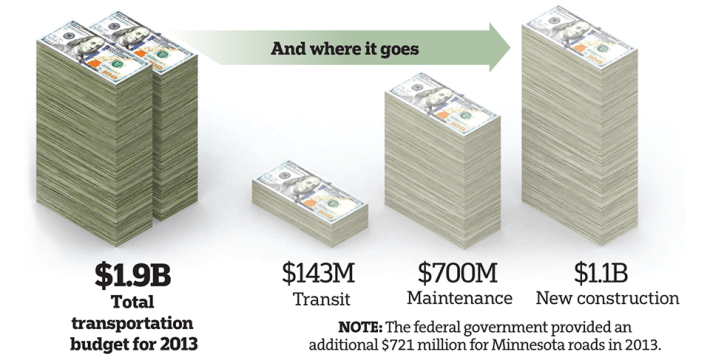

If you think that states have felt chastised in the last few years, think again. Here's a chart from the Minneapolis Star Tribune showing how Minnesota DOT divides its money between maintenance and new construction:

Doubling federal transportation spending wouldn't solve this problem. Pumping billions of additional dollars into state DOTs without reforming the current system could actually make it worse -- giving agencies license to spend lavishly on new projects that serve only to increase their massive maintenance backlogs.

A new report from the Center for American Progress finds that 50 percent of existing roads don't carry enough traffic to generate gas taxes sufficient to pay for their own maintenance. While raising the gas tax might change the equation for some of these roads, the level of subsidy is disturbing. The last thing we need is more money-losing roads to maintain.

The Vice story -- the one that's supposed to scare us into approving funding for transportation -- is actually a catalog of tremendous waste. The magazine cites Seattle's dangerously destabilized Alaskan Way Viaduct -- an elevated highway -- as an example of decay, then notes that at least $2 billion has been dumped into building the most expensive possible solution to that problem: an underground highway.

Seattle and the state of Washington could have selected a much cheaper alternative -- tearing down the aging elevated highway, replacing it with an at-grade boulevard and better transit options. Studies by the city actually found the surface transit solution would have moved as many people as the tunnel at a fraction of the price. But the region's politicians and transportation authorities chose the high-cost, high-risk path, and they may end up with nothing to show for it.

Vice also points to Cincinnati's aging Brent Spence Bridge over the Ohio River. But is money the answer, or does Ohio just need to make better use of the funds at its disposal? Elsewhere in the Cincinnati region, Ohio DOT has insisted on building a $1.4 billion highway to the eastern suburbs despite widespread opposition from the communities it's supposed to serve.

There are similar stories in most states -- DOTs willing to break the bank on gold-plated highway flyovers designed to shave 40 seconds off a half-hour commute, while neglecting important bridges and other assets that present real risks.

One voice of reason has been civil engineer Chuck Marohn, who's had to dodge threats from his peers because he challenged the orthodoxy that more infrastructure is always the answer. As he put it in a recent post on his Strong Towns blog: "American prosperity is not simply a function of how many roads, pipes and hunks of metal we can construct. Our infrastructure investments must work to support the American people, not the other way around."

Correction: An earlier version of this story said the CAP report found that only 50 percent of new roads carry enough traffic to generate revenues sufficient to cover their maintenance. The statistic actually applies to existing roads.