The Twin Cities region is reassessing the role of highways in its transportation system.

Like many communities throughout the country, Minneapolis-St. Paul is moving beyond the decades-old assumption that the only way to eliminate congestion is with more outward-stretching asphalt. This fall, officials in the Twin Cities voted to roll back highway expansions and increase access to transit options instead.

Local planners say it's time to acknowledge that the region simply can't afford to accommodate growth by building new highways.

“We couldn’t keep going on acting as if we were going to get money to build our way out of congestion,” said Arlene McCarthy, Director of Metropolitan Transportation Services for the Twin Cities Metro Council, which drafted and approved the new plan. “One county alone could easily consume all the money the region has. That’s the reality.”

With vehicle trips expected to increase 35 percent by 2030, regional planners estimate it would cost approximately $40 billion to even attempt to tackle congestion with traditional road projects. But only about $8 billion is expected to be available to the regional planning agency over the next ten years.

The goal of the Twin Cities 2030 Transportation Plan is to maximize the use of existing freeways by adding bus lanes or priced traffic lanes in shoulders wherever possible. The new framework will require increased emphasis on transit and other non-automotive modes.

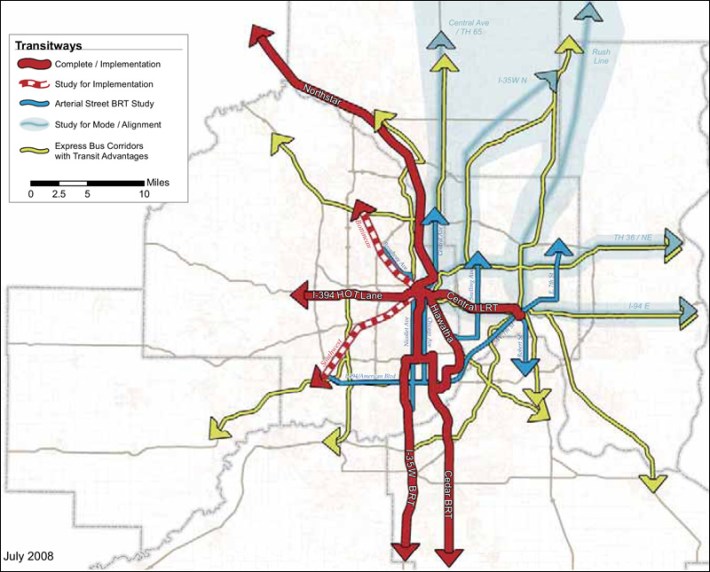

Rather than measuring transportation capacity in terms of traffic volumes, planners have focused on moving people. The 2030 plan calls for using congestion pricing to help encourage transit, carpooling, walking and biking. The Twin Cities envision a network of “transitways,” which will serve the region through passenger rail, bus rapid transit or express busways. Compact, transit-oriented development will be built in clusters along these corridors. The plan also calls for clustering jobs near transportation centers and encouraging mixed-use development, McCarthy said.

The overall strategy is to pursue high-benefit, low-cost projects. “We’re asking the question, ‘Can we provide the majority of the benefit at a much lower cost?’” McCarthy said. “We’re finding that we can do that.”

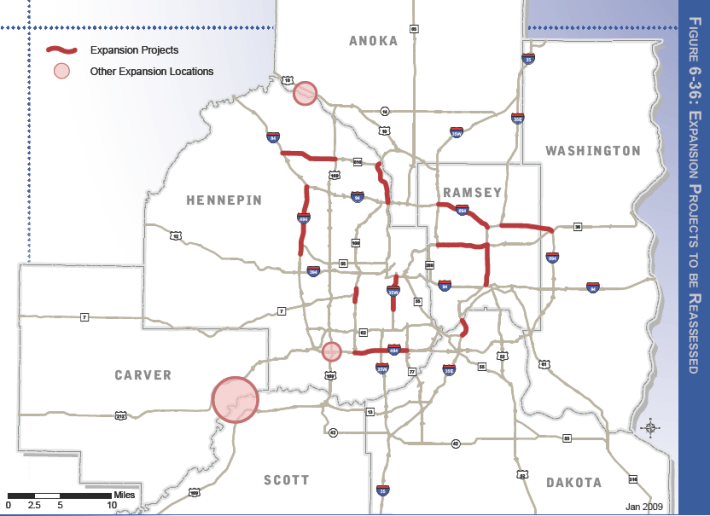

As part of the new framework, 14 previously planned highway expansions totaling $2.3 billion have been tabled. However, six "high-impact, low-cost" highway projects are still slated to move forward. Many of the remaining projects focus on the building of high-occupancy/toll (HOT) lanes, but traditional highway building is included to a limited extent as well.

Local environmental and business groups have been supportive of the proposal. Jim Erkel, director of the land use and transportation program at the Minnesota Center for Environmental Advocacy, said it will help ease water and air pollution in the region and prevent sprawl from consuming farmland. The plan, he said, should also help the region stay in compliance with the Clean Air Act.

“We’re going to be looking at less impervious surface,” he said. “Building in already developed areas should mean fewer vehicle miles traveled.”

In addition, Jeremy Estenson of the regional chamber of commerce told the Star Tribune in September that despite some reservations, overall the business group is behind the plan.

Of course, not everyone is thrilled. A group of suburban political leaders raised strong objections, noting that without highway expansion plans in place, the suburban counties would not have been eligible to apply for windfall funds like the federal support that flowed from the 2008 stimulus package.

“Some of us felt that we should have a more aggressive plan,” said Dennis Hegberg, a commissioner with suburban Washington County, which is growing rapidly. "There are a number of state and federal highways that need attention and I feel they're not being paid attention to." Still, Hegberg said he and his counterparts have accepted the result of the council’s vote.

One major catalyst for change was the tragedy that took place on August 1, 2007, when the I-35W bridge collapsed in Minneapolis and thirteen people were killed. The event prompted a tax increase to support bridge maintenance, and more generally, forced political leaders to take their responsibility for infrastructure maintenance seriously.

"After August 1, 2007 the ground shifted tremendously," said Erkel. “It seemed to take that to make the legislature realize that we had a lot of things to take care of."

The 2030 Plan, and its emphasis on maintenance, should help ensure the community avoids such tragedies in the future.

The plan puts the Twin Cities ahead of the curve in regional transportation policy from a national standpoint. But Minneapolis still lags behind places like Portland, Oregon; Arlington, Virginia; and Montgomery County, Maryland on issues such as land use and transit, said Myron Orfield, director of the Institute on Race and Poverty at the University of Minnesota and author of American Metropolitics.

Though the traditionally progressive Twin Cities benefit from having very strong land use statutes, they haven't been aggressive enough in enforcing those standards, he said.

Will Schroeer, policy and research director for Smart Growth America, agreed that the Minneapolis plan has room for improvement. Priced lanes offer some advantages, including the ability to recoup expenses, manage congestion, and create priority space for buses, Schroeer said. But the additional lanes still reinforce auto dependence.

Twin Cities officials acknowledge within the plan that the region already has a greater number of highway miles per capita than many comparable areas. The region built hundreds of miles of new highways in the 1960s, '70s and '80s. While the 2030 plan is a step forward, Minneapolis could have gained more ground on the nation's best-planned regions by just saying no to any new highway lanes. "It’s new capacity in an area which doesn’t really need new capacity," said Schroeer. "It’s better than regular capacity but it’s still not great."